The passage below is in English. If you would like to test your Irish please follow the link at the bottom.

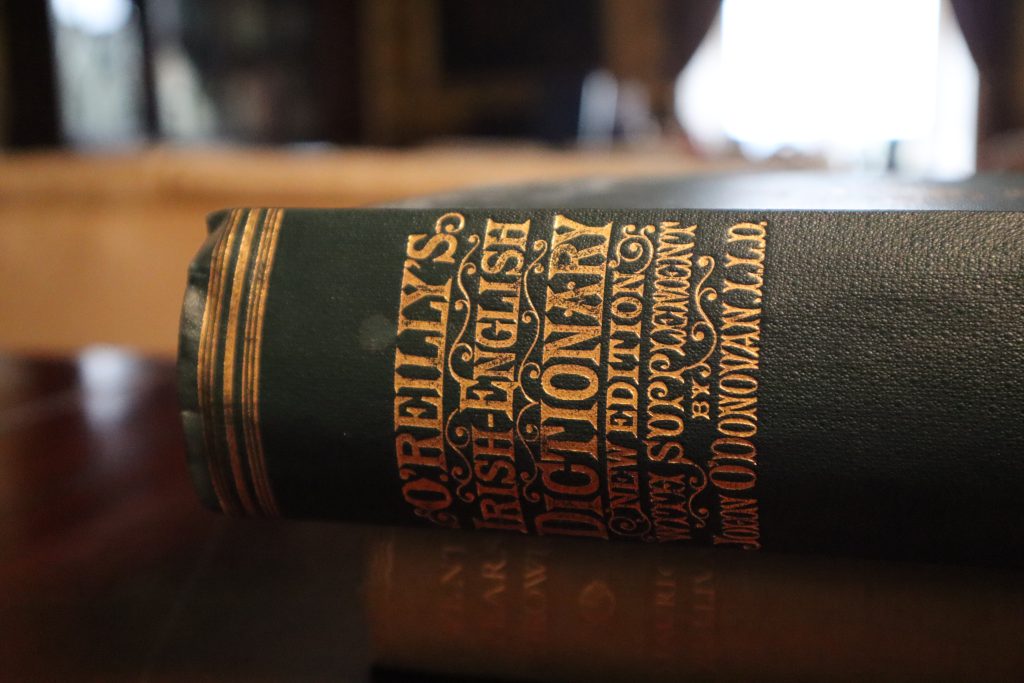

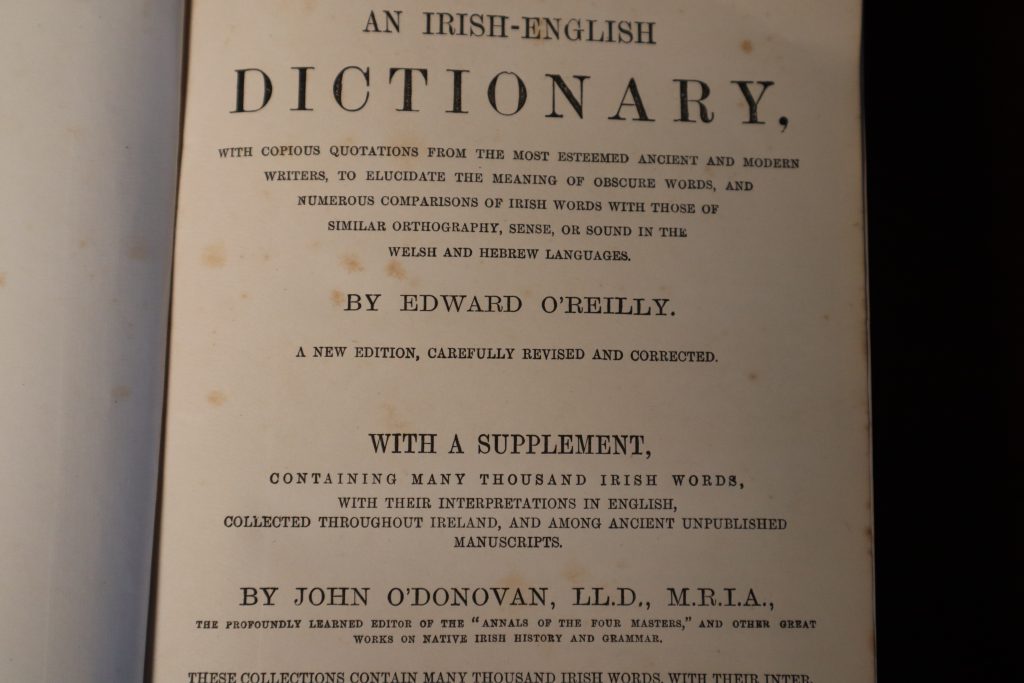

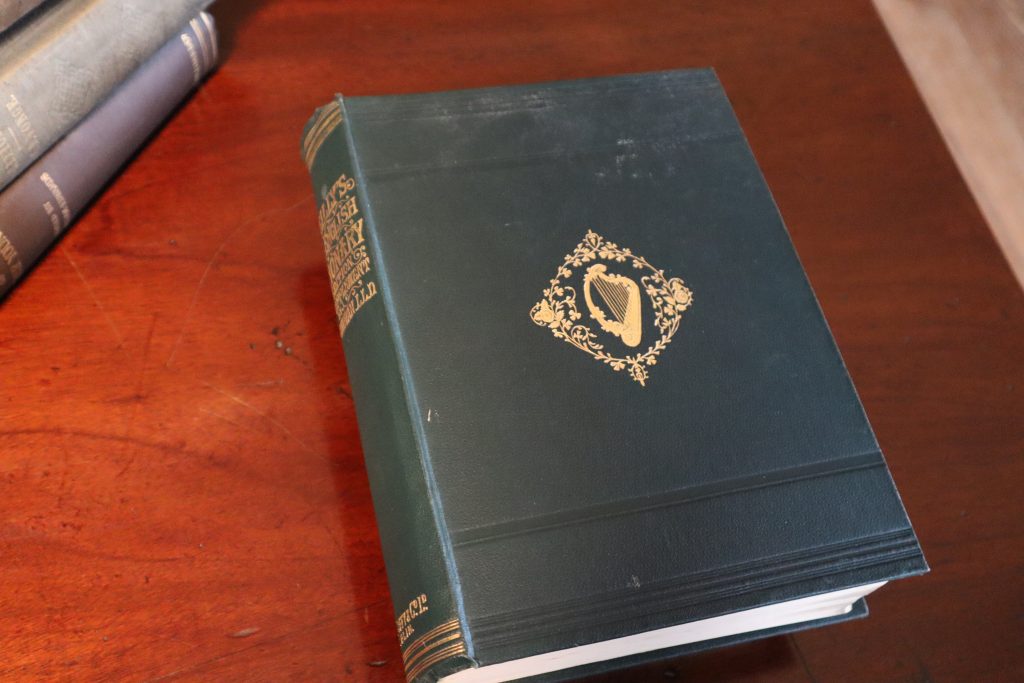

Among the most surprising books to be found in Strokestown House is this beautiful 1877 edition of Edward O’Reilly’s Irish-English dictionary, printed in the Cló Gaelach or Irish Script. First published in 1817, it was compiled by the self-taught Irish Scholar and lexicographer Éadbhard Ó Raghallaigh/ Edward O’Reilly, who despite not being a native speaker of the language devoted his life to the study and preservation of Irish manuscripts and the collection of traditional stories and songs.

Born in Dublin to a family originally from Cavan, little is known about his immediate family apart from his brother Andrew, a member of the United Irishman who later became a famous journalist and author specialising in France. He received very little formal education and instead taught himself Irish through the close study of a number of manuscripts which he purchased in 1794 from a young man who was preparing to emigrate. Through transcribing and translating these manuscripts he developed an impressive grasp of written Irish spelling and grammar, though according to his contemporaries his spoken Irish never reached the same standard, and some of the translation work he performed towards the end of his life for the Ordnance Survey of Ireland has been criticised (he was accused, for example, of confusing clann (family) and cluain (meadow) in a number of place names).

Despite these criticisms, O’Reilly is acknowledged today as among the most important Irish Scholars of his day, whose contribution to the study and preservation of Irish manuscripts through organisations like the Iberno-Celtic Society and the RIA played a significant role in laying the groundwork for the Gaelic revival. He also founded an Irish school in Dublin in 1810, and in the 1820s collected a large number of songs and stories from around Roscommon and Longford. He died in Dublin in 1830, having released a second edition of his dictionary in 1821 and apparently leaving a third unfinished. In 1864 the book was edited and republished by the famous scholar Seán O’Donovan/ Seán Ó Donnabháin, who also added a supplement containing ‘many thousands’ of words that O’Reilly had missed. This 1877 edition was published by James Duffy & Co. and includes O’Donovan’s supplement. The Dictionary also includes notes and annotations from Seán Ó Briain, the Bishop of Cloyne who published the first known Irish to English dictionary in 1768. Aside from the use of the Gaelic script, which was abandoned in the 20th century partly because of the difficulties it posed for printers and typists, the dictionary is dated by its spelling conventions, which pre-date the development of an Caighdean Oifigiúil in the 1950s. The dictionary therefore includes the ponc séimhiú, for example, and preserves older spellings of many words, such as ‘gaoidhilig’ (p. 371) instead of Gaeilge.

On the basis of its age, and presuming that it was bought new, it seems likely that this copy belonged to Henry Pakenham Mahon, the father of the house’s last occupant Olive Pakenham Mahon. There do not appear to be any Irish texts in the house, nor is there any reason to believe that any of the family actually learned Irish, but it is nonetheless interesting to find such a document in the library of an Anglo-Irish landlord with no known connections to the Gaelic revival movement. It is worth noting that in an interview recorded late in her life Olive appeared to take pride in the Gaelic origins of the name Mahon, again indicating the family’s complex and contradictory relationship to Irishness. The book includes a single handwritten note on the final page by an unknown author which refers to the famous dictionary of English Dialects composed by Elizabeth Mary Wright, and notes that the word ‘Breac = speckled’ (which readers may recognise from Snag Breac, meaning magpie, literally ‘speckled sneak/thief’). The book also contain an interesting bookmark advertising careers in the Pre-Independence Civil Service, promising ‘short hours, pleasant duties, good salarys [sic], long holidays, [and] good prospects’. It is unknown if any of the family seriously considered such a career.